Much before the uncertainties overtook Kashmir, an old city school dropout jumped into the labyrinth of the ‘cause’. Seeking answers to real life from reel life, Noor M Katjoo moved cadres, crossed borders, fought, was caught and eventually freed. The greying young man offers his version of history to Bilal Handoo at a time when curtains seemed to have fallen on his quest and the talkie that he famously used to undo the history he loved to hate

Men at work have left after making dust of a few decades old show. It is The End of Srinagar’s Regal Cinema. The cinema that sparked off rebellion in mid-eighties has been completely decimated.

But quite contrary to a much-talked about “spontaneous” reaction supposedly triggered by a film titled Omar Mukhtar screened at Regal, a man who burned Sheikh Abdullah’s poster is alive to admit: “More than a spontaneous reaction, it was a well scripted plan!”

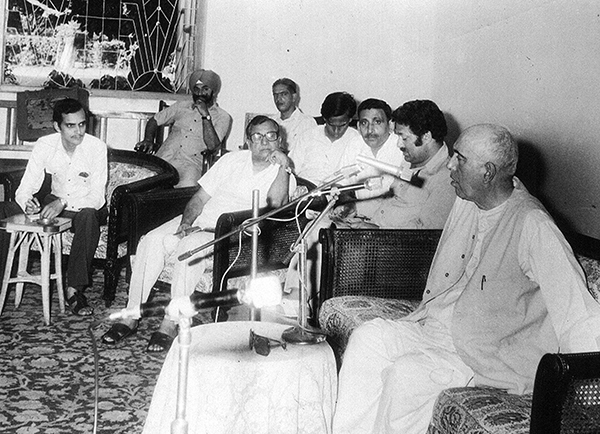

These days Noor Mohammad Katjoo, 50, of old Srinagar’s Malaratta locality is counting his days quite miserably. Just 3 kms away from the dismantled cinema, he lives in a typical medieval house of old city.

A narrow and dark staircases lead to the first storey of his house. A vehicular noise piercing his room through a window is quite deafening. Besides speedy vehicles plying on the street below set tremors in his house.

As he sits near his window and sets his gaze outside, he starts recalling his past.

Katjoo was known as the “daredevil of downtown” until his torment began. Over the years, his ‘macho-man’ image has totally diminished.

He still remembers Regal and other eight cinemas of Srinagar as big business houses before a militant outfit ‘Allah Tigers’ and its chief, Air Marshal Noor Khan announced a ban on cinemas and liquor bars through local dailies on August 18, 1989.

The motive behind the ban was to create an atmosphere for waging full-scale rebellion against Indian rule in Kashmir. But despite the ban, cinemas functioned until growing public outcry and death threats to owners stalled the popular public hangouts on December 31, 1989.

And soon deserted cinemas were turned into notorious detention centres with barbed wire windows, bunkered gates and bullet-torn walls.

But among the cinemas, Regal was known for triggering a rebellion. In the summer of 1985, Director Mustafa Akkad’s film, Omar Mukhtyar starring Anthony Quinn was screened at the Regal in Srinagar’s city centre, Lal Chowk. The film showed Libyan guerrilla leader fighting against his country’s occupation.

The inflamed young men coming out of Regal then torched Sheikh’s poster. “But that reaction wasn’t all spontaneous,” claims Katjoo, defying the prevailing notion that the film triggered the reaction. “It was all pre-planned by a group of young men fighting against the occupation. The motive behind the move was to send a strong message.”

The film, which was running houseful, was forcefully taken down in the first week itself by the authorities.

But the plot of the script that followed was akin to any Hollywood blockbuster.

***

Preview

My name is Noor Mohammad Katjoo. I was born in 1964 in the milkmen family of Old Srinagar’s Malaratta locality. I was breast-fed by seven lactating mothers. The ritual meant auguring longevity, health and good fortune for a child. I was the only brother among six sisters. I studied in a local private school up to 7th standard before I grew disillusioned with studies. I then started working as a coppersmith. I was known for my skills to draw beautiful patterns on copper utensils.

Stony Affair

During those days, stone pelting was a common feature of downtown. I would only participate in stone pelting if I would hear pro-Pakistan slogans being raised. It was mid-seventies. Two years later in 1977, while walking near old city’s Naid Kadal, I was arrested by police for the first time. I was lodged in Zaina Kadal police station. Later the cops told my father: “Your son has become a nuisance for us. Better keep him away from stone pelting. Or, the consequences will be too bad for him!” I was later released. But who gave a damn to what cops were preaching.

Introducing Mushtaq Latram

After walking out of prison, I was leading a normal life for a while. And then one day, in early eighties, one local shopkeeper told me: “We should do something for the freedom of Kashmir.” I didn’t understand the real motive of that man. But I casually replied: “But what can we do?”

“We can do many things. But first tell me, can you arrange some boys?”

“Yes, I can.”

“Great! Okay then, meet me soon with other boys,” he said and left.

The man was Farooq Ahmad Khushu of Bohri Kadal. I soon understood that he was up to something.

Meanwhile, I gathered some boys. One among them was Mushtaq Ahmad Zargar aka Mushtaq Latram.

Latram was a coppersmith artisan like me. I told him: “Look, we are recruiting local youth to work for the freedom struggle of Kashmir. What do you say? Would you like to join us?” Without giving any second thoughts, he blurted out: “Yes! I would love to be part of it.” But before giving him a nod, I strictly instructed him to stay quiet about our plans.

That is how I introduced Latram to the freedom movement of Kashmir.

A ‘Grave’ Meeting

Khushu directed me to meet at Malkhah [the largest graveyard of valley in old city] with those boys. In that secret meeting amidst graves and under bushes, Khushu told us: “I hope you must have prepared your minds well to face any consequences by choosing this path. But let me assure you all, you don’t need to worry about anything. We will act as per plans.”

The birth of Al Maqbool

In the same secret meeting at Malkhah, we decided to float a pro-freedom party. We named it Al Maqbool after Mohammad Maqbool Bhat who was at that time incarcerated inside Tihar Jail. To run the party, each member would pay Rs 300 per week. For the next two years, we continue to unfurl Pakistani flags at many places of Srinagar as a mark of protest against Indian rule.

During those days, unlike today, Pakistani flags were symbol of Kashmir’s Independence. Other than Pakistani slogans and flags, everything else was simply viewed with suspicion.

Mission Pakistan

In later part of 1982, Khushu told us: “Be ready, we have to go to Pakistan!” The news delighted us. Mushtaq Latram and another member were chosen for the first visit.

One fine day, the duo left for Pakistan. They met their guide at Baramulla. The guide demanded money before taking them along. But as Latram gave him money, the guide ran away. This forced them to come back. They were clearly instructed to give money to guide only on Pakistan border. But somehow, they couldn’t stick to the plan. Everyone termed it a human mistake and the matter was put to rest.

And soon, the preparation for another Pak visit resumed. This time I and another party member, Farooq Ahmad, not Khushu, were chosen for the visit. We both were cautious and went ahead with full preparation.

A mysterious military task

Upon reaching Pakistan border, we were taken inside a room where a Pakistani military man in civvies met us. “So, what is it that you want to do?” The man quizzed. “Sir, we actually are members of Al Maqbool…” I replied. “Yes, yes, I know. There is something you are expected to do,” he said.

“What are we expected to do?”

“Simple, Lawo aur leejao,” he replied.

“But, Sir, what can we give you?”

“You can give us enough. To begin with, do one thing, note down numbers painted on the rear end of the Indian army vehicles and send it to me,” the man directed.

And with that, we started leaving for home, but he stopped us, saying : “Do you need any money?”

“Not money. But, can you give us some ammo?”

He gave us a pencil bomb before we left. After paying Rs 7,000 to our guide, we set foot back inside the valley.

Once back to old city, we informed Khushu about the plan. We all agreed to do it. We dispersed in different parts of valley to note down numbers on army vehicles. I myself went to Baramulla. Without letting anyone to sniff about our activities, we kept noting down the numbers for close to 50 days.

Farooq Khushu finally dispatched them to Pakistani border through a reliable guide.

But till today, I have failed to conclude the purpose of those numbers.

A Shocker from Tihar

In 1983, we sent two of our members to buy arms and ammo from Doda. They brought three pistols besides some explosives. We again met at Malkhah and discussed the strategy. That meeting was very grave for all of us. The news of Maqbool Bhat’s possible hanging had spread. Neelkanth Ganjoo, the Sessions Judge of Srinagar had sentenced him to death. We wanted to do something, but we couldn’t do anything.

By February 11, 1984, India hanged Maqbool Bhat inside Tihar Jail. Although expected, but the hanging of our hero was a shocking news for us.

We started agitation. A fierce stone pelting began. We torched a vehicle in Bohri Kadal Chowk in protest. Even then, our anger couldn’t vanish.

Extensive discussions and debates into the factors behind Bhat’s hanging followed.

During the same time, we made up our minds to carry out a series of bomb blasts. On April 22, 1984, we did three bomb blasts. One bomb blast was triggered near Satellite in Badam Bagh. The second bomb blast at Srinagar’s High Court, because the hanging of Shaheed Maqbool Bhat was written there.

I was tasked to trigger a bomb blast at the house of Neelkanth Ganjoo in Karan Nagar. The motive was not to kill anyone, rather to send a strong message. Ganjoo was later shot dead in 1990. He was among the first persons to be killed.

After these bomb blasts, I and Mushtaq Latram went to the newspaper office and gave them a written note. We had claimed the responsibility of the bomb blasts. While Mushtaq went to Aftab office; I went to Srinagar Times. The next day the newspapers reported that some unknown men affiliated with Al Maqbool visited their office and claimed the responsibility of bomb blasts.

Hoisting Green across Jammu

Before Maqbool Bhat’s first death anniversary, we were planning to create a big impact. As we met, it was decided: “We will hoist Pakistani flags simultaneously at Srinagar and Jammu.”

On Feb 10, 1985, I along with my other party member, Altaf left for Jammu.

It was already night when we reached Jammu. In the darkness, we kept roaming with a bag full of Pakistani flags. We were about to hoist first flag when someone shouted behind us. It was petrifying call. As we turned back, we saw a cop staring at us. “What are you doing here at this hour?”

“Sir, we have lost our way. We don’t know how to reach Jamia Masjid,” we replied.

From his gestures, it was certain that he was a very tough cop. “Okay, that’s fine. But what are you carrying inside this bag,” he asked, very sternly.

His demand was alarming. To distract his attention though, I took out a pear from the bag and insisted him to eat it. “No, no. There is no need for this. Do one thing. Just follow this route, you will reach Jamia Masjid,” he replied.

We sighed relief and walked away. Immediately, we did our task. Till the dawn of next morning, we kept hoisting flags.

Once done, we went to Jamia Masjid. We shortly left and boarded first vehicle for valley. To force the driver to leave immediately, we told him: “Please, move fast, our grandmother is very ill.”

The trick worked. The driver drove fast. By late afternoon, we were back in valley.

The next day, both Jammu and Srinagar based newspapers reported the episode. And thus made authorities alarmingly alert.

Joining Tala party

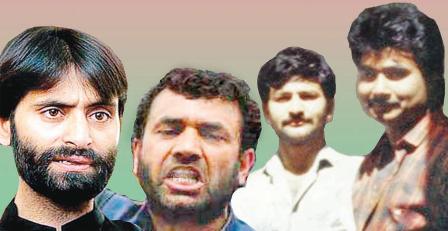

In those days, I was part of another popular party called Tala Party. It was also working for the freedom movement of Kashmir. Yasin Malik, Javaid Mir, Nayeem Khan, Mushtaq Ul Islam, Shakeel Bakshi, Showkat Bakshi, Firdous Shah, Iqbal Gondur, Fayaz Gondur and others were the part of it. We would meet at old city’s Bohri Kadal. We had named the place as Akaiel Takhte.

For us, stone pelting was a sign of resistance.

Interestingly, once on July 13, we went to throw stones at National Conference gathering at Khwaja Bazaar in old city. But the NC mob caught Yasin Malik and roughed him quite badly. They drenched him in a mud pool. Somehow, we took him away. After washing him up, we took him to SMHS hospital for treatment. We didn’t reveal his real name for the fear of his arrest. Those days, police and CID men in civvies would often make rounds around the hospital.

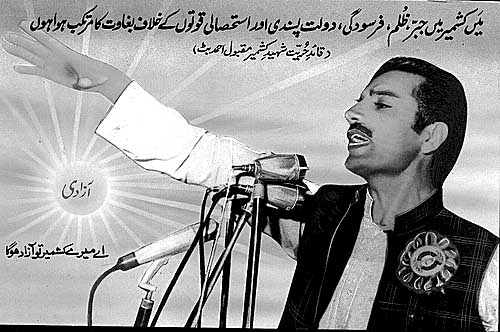

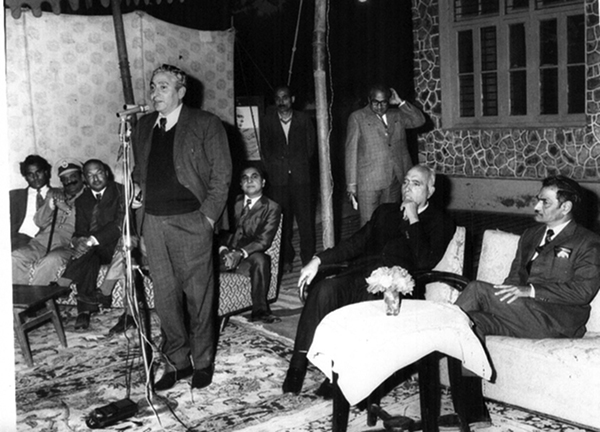

A plot behind Omar Mukhtar

On one fine day in 1985, members of Tala Party met at Srinagar’s Eidgarh. In that meeting, it was decided: “We will burn Sheikh Abdullah’s poster after watching ‘Omar Mukhtar’ at Regal Cinema!” Everyone in the meeting was instructed to watch the movie with one’s own pocket money. Everyone was clearly instructed to watch film from Stall, the middle part of cinema hall. It was a common understanding that Stall would remain crowded by ruffians. And in case of police raid, those men would come to our rescue.

On the fateful day, we went to watch the show between 1 PM and 4 PM. At interval, I asked my fellow members: “Have you brought Shiekh Abdullah’s poster?” “No!” Their reply was surprising.

Later, I understood that everyone had thought that some other member would bring the poster. As a result, none had brought it.

So, I walked out of the cinema hall along with two other members to get the poster.

We passed through Regal Lane and reached Palladium Cinema where we saw a big life-sized portrait of Sheikh Abdullah hanging on the wall of a shop in the narrow lane. We greeted the shopkeeper and told him: “Today is the engagement ceremony of our brother. He is pressing hard for the photo of Bab [Shiekh Abdullah]. He says, without Bab’s photo, I won’t take part in the engagement. Since morning, we have been searching the same but couldn’t get one. Now, we spotted one in your shop. Please help us. Give us this photo. We are ready to pay anything for it.”

The shopkeeper agreed. We handed over a hundred rupees note to him and walked away. We broke the glass frame of Sheikh’s portrait, folded his photo and kept it safe in pocket. We shortly joined our members back in the cinema.

Later, as per plan, we charged out of the cinema along with Sheikh Abdullah’s photo. I, Yasin Malik, Iqbal Gandroo and many other youth pitched slogans. The people coming out of the cinema hall joined us. As we tried to set Sheikh’s photo on fire, somehow it didn’t catch fire!

I and Javaid Mir ran towards nearby Shakti Sweets shop. We drained all the kerosene from a stove in to a glass. We rushed back to the spot. I sprayed kerosene on Sheikh’s photo and set it on fire.

It created a great scene on the spot. But soon, a police party rushed to the spot and we all ran away. I ran towards the Bund. But the police party was still after me. A few gamblers saw police behind me. To appease police, they shouted: “Thief, thief…” They caught and handed me over to them.

I was lodged in Kothi Bagh police station for 3 hours. And then, I was taken to Srinagar’s Red 16 interrogation centre. I was kept there for 16 days. After that I was again taken to Kothi Bagh from where I was taken to Central Jail, where I was released on bail.

Disintegration of Al Maqbool

After coming out of prison I came to know that many youth were detained. Freedom fighting parties like the Holy War Fighter’s group, Al Jehad and our Al Maqbool faced police raids. I, along with my other members of Al Maqbool was arrested. We were arrested under TADA. The act denied bail for sixteen months. We subsequently faced two year jail term. But not many endure the life of a prison. I could see how Mushtaq Latram broke down a number of times in jail. He held me responsible for his plight. But then, time passed on.

Mass Mobilisation

Two years later when we walked out of the prison, the preparations for an armed struggle were on full swing. I met one friend who told me: “Kashmiris are going for armed training to Pakistan administered Kashmir.”

His words also motivated me. I too made my mind to go for it. But Mushtaq Ul Islam stopped me, saying: “Stay back and guide aspiring Kashmiris from valley only.”

I agreed. But I had to start afresh. My parent outfit Al Maqbool had disintegrated. My former members had shifted their bases to other militant outfits. Everything was happening so fast. There was so much tension in the air.

A knock from HAJY Group

And then one day in 1988, Javaid Mir, Ashfaq Majeed Wani and three others showed up at my residence. They gave me arms and ammo for custody. It was the beginning of armed uprising. They were fresh from their Azad Kashmir visit. They had received arms training. And also, they had brought lots of ammo with them. I was clearly instructed: “Take care of these sacks. They are loaded with bombs and weapons!”

In the afternoon of that day, Javed Ahmad Shawl, the man who was later put under enforced disappearance, saw the weapons at my home. He reprimanded me: “It might land you in jail once again.” I brushed his concern aside.

Later that day, as it started getting dark, I took out a pencil bomb from the sack and went to attack Khanyar Police Station. I bombed the police station and ran away.

A fresh Warrant

A month later, I learned that a fresh warrant has been issued against me. It was related to Omar Mukhtar incident. Section 112 was imposed on me. On the same day, I went to meet my lawyer at Srinagar’s Lower Court. While discussing the possibility of my case, someone shouted behind my back: “Hands Up!”

As I turned around, I saw a party of police and paramilitary personnel staring hard at me. I was handcuffed, taken outside the court and bundled inside a police jeep. I was taken to Rajbagh police station, which was turned into an interrogation centre.

For the first two days, I remained tight-lipped. But I was shocked when cops told me: “So, it is you who threw that bomb on Khanyar Police Station!” I feigned ignorance.

“Do you think, we don’t know anything about you,” the cops started grilling me. Many questions followed.

I soon learned that some CID man had spotted me while running from the spot after throwing that bomb. But I continued to plead innocence.

To break my resolve though, they arrested my mother. She was put behind the bars for three days. But even then, I didn’t confess. Be treouhes pate treodey, I was hooked to the ceiling. That torment continued for three days before I couldn’t take it anymore: “Okay, please leave me. Yes, I threw that bomb!”

But even then, I wasn’t taken down until I told them:

“I have arms and ammo at my home!” I was briskly taken down. And another spell of questioning began.

“Where from you get that?”

Fearing reprisals, I confessed: “I was given its custody by Javaid Mir and others.”

But before police could have raided my residence to seize the arms and ammo; my mother had already flushed them into Jhelum from Zaina Kadal.

Finally, they released my mother. And, I was taken to Central Jail after being slapped by Public Safety Act (PSA). Shortly, I was taken to Hiranagar Jail.

I met Mohammad Ashraf Sehrai, Ghulam Nabi Bhat and others there. Sehrai too was booked under PSA. He helped me to sustain in prison. He would recite Surah Yousuf to me whenever the longing for home would trouble me.

One year later, much to my surprise, Shabnum Gani Lone sent her lawyer with a bail for me. I was told by the jail authorities that my PSA has been quashed. In the beginning of 1990, I walked out of the jail.

Going Sarhad Paar

I had distanced myself from the freedom movement for a while after coming out of jail. But I couldn’t remain detached for too long. “Don’t sit idle. Prepare youth for Azad Kashmir,” my friend, a head of Al Jehad armed group, told me. He gave me Rs 10,000 as travel and food expenses. Already, some young men of my locality were insisting me to take them to Azad Kashmir for training. I called them up and we left for our destination.

“I am going to fetch charcoal consignment from Kupwara,” I told my mother before leaving. “I will be back soon.”

We met our guide at Kupwara who safely took us to Azad Kashmir. I saw a sea of Kashmiris already turned up for the armed training there. I and other nine Kashmiris were sent to Alaqaaye Gair for 40 days armed training. That area was surrounded by red mountains. Our training was similar to Pakistani army.

After training, we were taken to a camp in Muzaffarabad. I soon learned that launching of groups had been put on hold. With the result, I spent the next one year inside the camp itself.

Each one of us was given Rs 20 per day as pocket money, besides meals.

Salahudin and Green Army

Almost one year had passed when I met Hizb chief, Syed Salahudin in the Pak camp. He was my good old friend. In the past, we were both associated with stone pelting. Besides, I had helped him during Muslim United Front (MUF) election in 1987. He told me: “Would you head a new party?”

“Which party?”

“Green Army,” he said.

“I will give you twenty guerrillas. Be the chief, return to valley and fight against the Indian occupation.”

I thought over his offer. And I soon realised that it was the only way for me to return to Kashmir. I accepted the deal.

“What I am expected to do?” I asked him.

“In the name of Green Army, you have to do one single action,” Salahudin said.

He handed over a letter to me. Besides, he gave me Rs 40,000 for journey back home.

“But I need a pistol,” I demanded.

“Don’t worry,” he assured, “you will be given one at PaK border.”

I was chosen Ameer or head of the group and left toward Pak border. We spent the first two days there.

I saw a group of young Kashmiris coming toward the border. They were coming for arms training. I saw a 8th standard student barely 13-year-old in that group. After interaction, that boy cried and told me: “Please, take me back to mummy. I want to go back to my mummy…”

The boy kept insisting. The treacherous journey had disillusioned that kid from Srinagar’s Rainawari locality.

I met a Pakistani official at the border who was receiving the Kashmiri groups. I told him about that kid. “Just look yourself, who they are sending for arms training,” the official told me.

“So, what shall we do now,” I asked the official.

“Whatever you say,” the official replied.

“I want to take him back to Kashmir with me,” I said.

The official agreed.

As we were still on Pakistani border waiting for instructions, I told that boy: “Would you like to see Pakistan before returning home?”

“Yes,” he replied.

I gave Rs 2000 to one of my group members and told him to take the kid to Lahore and show him the Shahi Masjid and other places.

Two days later, they joined us back on the border. The kid was very happy.

Meanwhile, we were instructed to collect arms and ammo. We were provided with five guides. And each one of us was given Rs 1500.

The kid was also given weapons. But they were too heavy for him. I talked to the official: “Look, at least, the kid should be spared from weapons.” “It is mandatory,” he replied.

To relieve the kid from the burden of gun, I gave Rs 1500 to one of our five guides to carry his weapon. The Pakistani army bid us adieu near a mountain, saying: “Your journey begins now!”

Thus began a treacherous Journey

We began climbing the peaks. From 7 AM in the morning to 8 PM in the evening, we continued climbing. At one spot, our guides instructed us to take some rest. To our shock, four of our guides gave us slip and fled.

“Look, our guides have left us in this wilderness,” I told my group. “It is better that we should go back.” But my idea was strictly opposed.

“We have still one guide with us who can safely drop us at home,” one of my group members said.

“We are returning home after one year, we shouldn’t move back. And who knows, whether we will get another chance or not,” said another.

“I am the only brother among four sisters. I have already lived one and a half year without my family. We should try to move on,” one more said.

Everyone insisted for a homecoming.

Meanwhile, one night passed in the wild.

The next day, I enquired from our last and the only guide: “Do you know the way to reach valley?”

“Don’t worry, I will surely take you home,” he assured.

After this assurance, we started moving downhill.

In the mid-way, we saw another group of twenty boys returning from Azad Kashmir along with their five guides.

I told them to stay cautious and informed them how our guides ditched us. That was a Hizb group. They too made me their Ameer. And I began leading the two groups with total forty guerrillas.

Our guides clearly instructed us to move in a single line. Besides, instructed: “Don’t smoke!”

As we started trekking downhill, we saw nine tents pitched on the dry canal below. I sensed danger. “Let’s take other route,” I told our guides. “I think, it is dangerous to move ahead.”

But the guide assured: “Don’t worry about the tents. Nobody dwells inside them.”

With that assurance, we resumed our walk.

An Ambush

It was already getting dark. I heard some creeping noises while climbing down. I didn’t read much out of them. But the moment we passed by those tents, a thunderous gunfire shook us up. As I turned back, everyone had disappeared from my sight.

I ducked for the cover. And straight away, I spotted one of my group members falling flat on the ground. “Please, save me. I am the only brother of my five unmarried sisters,” he pleaded before me. “So am I,” I told him in an attempt to calm him down. We both stood motionless under grass. I began making sense of those creeping noises, which I had heard while climbing down the hill. Mixed feeling of both regret and rage overpowered me.

And just then, I turned my head around and spotted one guide ducked on ground. Bullets were being pumped on us from all sides. It was an ambush.

I grabbed the guide’s right hand and told him: “Let’s move back to uphill and help others there.” The guide abused me before saying: “If you want to die, go and die there. Don’t drag me into this anymore. My task was to take you from Pakistan to Kashmir. My task is over. Don’t expect any help from me now.”

He sounded outrageous. But I maintained my cool. He shortly resumed: “Better take those white shoes out. Or, you will be caught!” I did as he said. But the moment I took my gaze away from him, he quickly disappeared in that grass cover. Everything was happening so fast that my mind almost stopped working.

The two of us were still hiding under grass cover in that dry canal. After sometime, the firing stopped. Now, we started crossing the canal. And just then, I saw one group member lying dead in the middle of the canal.

My group member insisted to take that martyr out of the canal. As we moved closer to him, he was breathing. We put him in a grass and rubbed his feet to restore his consciousness. As he regained his senses, he told us that he had fallen from the hill when firing began. He had broken his front tooth and bruised his body. Due to the impact, he was lying unconscious in the canal. We spend that night hiding in the grass.

Deadly Announcement

The next day, army announcement through public address system woke us up: “If you surrender, we promise you safety, and safe passage to home.”

I could see huge posse of Indian army pouring on the spot through the grass cover. They soon conducted the search operation. They came closer to us. I instructed my two group members to stay quiet. But we cocked our guns and prepared to put up what appeared the last fight of our lives.

But four members of our group hiding nearby raised their arms up to surrender. In a flash, army men punctured their bodies with a barrage of bullets. They fell dead back in the grass. The announcement was nothing but a trap.

After a while, I saw three more group members appearing hands up from the snowbound hill nearby. They met the same fate. Every killing was simply distressing.

Unkept Promise

But probably what made me numb was the sight of that kid from Rainawari. I saw him lying dead in a pool of blood on snow. For the time being, his cries for mother echoed in my ears. His killing simply broke my heart. I am still feeling guilty for not arranging his reunion with his mother, his mummy.

For the next day and night, we remained hidden under grass cover before we decided to move on. “But where shall we go,” my two group members asked. “Let’s search for something. Or, we will die from hunger and exhaustion,” I replied.

I had a bullet wound on my toe. Besides our exhausted bodies wouldn’t carry weapons. So I bundled all the guns with my jacket and buried them under grass. We only carried bags and money with us.

For the next five days and nights, we wandered in the woods. We saw jackals and were almost frozen to death by the biting cold. But to our good luck, we saw an abandoned cottage. We lit fire there to warm ourselves.

As we resumed our walk, we shortly located a village. It was such a delightful sight. Soon we started planning our homecoming. “Let’s give Rs 40,000 to someone in the village to drop us home,” I told the duo with me. They agreed, but in a fit of joy, they said: “We should go back and collect our weapons.”

Those were incredible words I have heard from their mouths. I told them that it was silly on their part to even suggest resuming of that arduous journey. They understood. And we started moving toward the village.

A twisted Trap

As we inched closer to the village, Indian troops suddenly emerged from the ground and shouted: “Hands up!”

It was a shocking arrest. Our pockets were searched. They seized Rs 40,000 from my pocket. But surprisingly, they kept Rs 1500 back in the pockets of my two group members.

They had caught another five Kashmiri youth returning from training. They were not from our group. Their pockets were also searched. A big amount from their pockets was also seized.

Soon, army officer visited. He asked one among those five Kashmir youth: “Where have you kept your money?” The youth quite innocently replied: “Sir, your men have already taken that.”

The reply infuriated the officer. He flashed a sword and struck it hard on the throat of the youth. He bled profusely and fell dead to the ground.

I realised the cost of speaking truth. My two members quickly handed over their Rs 1500 each to army officer. But I had no money left. In fact, I had given my Rs 1500 granted to all of us on Pak border to a guide for lifting that kid’s weapons.

“Sir, I lost my money somewhere in the woods,” I told the officer. “So you lost your money, right?” he asked in a pretentious manner. I nodded in affirmation.

“Are you sure that none of us took your money?” he quizzed, to which I repeated my earlier reply. “Just listen, what this man is saying,” he almost shrilled. “We are not thieves. I killed this man because he made a serious allegation against us!”

A Slip

Later that evening, we were called inside the tent. And, one by one, we faced the queries of the high-ranking army officer. We hadn’t yet revealed to them that we were coming from Azad Kashmir.

“So what brought you here?” the officer asked me.

“Sir, I along with my group was going for arms training to Muzafarabad. But sudden firing dispersed us and we kept roaming in these woods.”

But one of my two group members told the officer: “We were returning to valley after arms training. Also, we have abandoned our weapons in the woods.”

I couldn’t blame him for telling the truth. We could literally see death staring at us.

The officer then called some army men. He directed them to accompany us to recover the dumped weapons.

A Morgue inside Jungle

We were thrashed on our way back to jungle. For three days and nights, we roamed tirelessly. Much to our shock, we saw scores of Kashmiri youth martyred in that jungle. Most of the dead bodies were still oozing blood. Some bodies were disfigured. A few of them were brutally cut. I don’t have proper words to describe that scene.

“Please allow us to bury them,” I requested the accompanying army major. But his reply shocked us more: “How many will you bury? This jungle is full of such bodies! Be ready, you are soon joining them.”

A few kilometres ahead, we were left even more shocked. We saw the bodies of slain Kashmiri youth hanging from the tree branches. It was so scary; rather, a nightmarish sight. “Can we please bring them down?” I asked the major. But he gave me his usual reply: “Don’t plead for them. Think of yourself. You will be also hanged like this, if you fail to recover those weapons.”

The Scandalous Secret

At last, we reached near the canal where we were ambushed. “We did that firing,” the major revealed, “and killed 27 armed trained Kashmiri youth.” It was an unexpected revelation. Somehow, I began joining the dots. The series of incidents that happened to us while returning from PaK made a perfect sense now. Everything seemed scripted: Fleeing of our four guides, uninhabited tents in canal, mysterious disappearance of our fifth guide and the army ambush.

The major, meanwhile, continued: “Rest of you managed to give us a slip. And I know it, you three are among those survivors.”

We searched for the weapons. They were untraced. This annoyed the army party who informed the officer at base camp through wireless: “Sir, these men are cheats. They are only buying time. They have no weapons.” The officer instructed them: “Kill them and return.”

Our ropes were untied. Three of us were lined up in a single row. After chanting some mantra, they pointed their guns at us. They were about to shoot when I suddenly cried out: “Please wait!”

They lowered their guns: “What happened?” In a trembling voice, I requested: “Sir, may we offer one last prayer before death?”

The request was accepted. With no water around we went ahead with our prayers. We cried a lot during prayer. As we knew that this would be our last prayer.

We were again made to stand in a single line. They again cocked their guns and pointed them at us. They were about to pull the trigger, when I again shouted: “Wait!”

The army major pushed up the muzzle of the gun. A bullet pierced through the air. My memory had rushed back. “I have kept the weapons under that grass cover,” I told the major.

But a junior rank army officer confronted the major: “We should have killed them on first day itself. But you seem to have a soft corner for them. It is already fifth day, damn it! They are getting on our nerves. Why can’t we kill them and leave?”

“Look, I am answerable to higher ups, not you,” the major replied. “I know these buggers are lying. Let’s give them one last chance. We otherwise have to kill them, right?”

The major took me to the spot. And much to our relief, I found the weapons wrapped inside my jacket.

“Did you see that,” the major told his subordinate, spreading a deep smile of conquest. “I wasn’t letting them to take us for a ride for nothing. I knew what I was doing.”

Spitting Spree

We were soon taken to Machil village. Indian army ordered all villagers to come out of their homes and assemble inside an open field. After all had assembled, the army ordered each and every villager to spit on our faces!

Those villagers were helpless. They were forced to oblige the order. Some of them even whispered an apology while spitting on us.

After spitting, army directed us to chant a slogan: “One who aspires to go to Pakistan is a bastard!” In presence of whole village, we kept chanting till our throats dried up. Later we were dragged to a nearby army camp.

The Scripted Ploy

Inside the camp, I was taken to the room of the army officer. I saw the same letter in his hand, which Syed Salahudin gave me before leaving the training camp in Azad Kashmir.

“So you belong to Green Army, eh?”

I feigned ignorance and replied: “I don’t know what you are talking about?”

“Look, don’t try to be so smart with me, okay?” he warned. “I have read the letter. It carries your name: Noor Mohammad Katjoo alias Haider. I also know that Salahuddin has asked you to drop this letter at an address in old Srinagar’s Kawa Mohalla.”

The officer caught me totally off guard. He seemed to know everything about the plan.

He then tore the letter into pieces and put it inside a coal blazer in his room.

“I want you to understand something very clearly: Just forget Azadi! You will never get that,” the officer boasted. I stood motionless.

“Do you know something? We were waiting to hunt you down in the woods,” he revealed, making my doubts clear. “But you took two extra days to show up. You were returning from PaK with a group of twenty men, weren’t you? But you surprised us when instead of twenty, you came with forty. We gunned down 27 in your group near the canal, besides arresting other 10. And then we laid a trap to hunt three of you down…”

“But how did you know about us and our plan?” I interrupted.

He smirked before replying: “Who else can inform us than your own people! We even knew the route you were coming from.”

The officer melted away all my doubts. Our guides were indeed our tormentors!

A doomed torture

The three of us were imprisoned in Machil camp. We were tied with a single rope. Our hands were tied. They would drop our food on a cement floor before directing us: “Eat like a dog!”

Inside our prison cell was a tin box. We used it for peeing. We were denied drinking water. Instead, we were made to drink urine stored in that tin box for about 15 to 20 days. The torture didn’t end there. Army men used to beat us with high tension wire. Besides, they continuously slammed my head with the wall. As a result, I suffered from a serious concussion.

After twenty days, we were shifted to another camp where a fresh spell of torture started. Shortly after that, we were taken to Badami Bagh Cantonment for 70 days. After receiving a renewed interrogation at Badam Bagh, we were shifted to Kot Bhalwal for one year. And then, we were shifted to Ramnagar where I was finally bailed out after four months.

A deteriorated daredevil

When I walked out of the jail in the later part of 1992, I was rendered neurologically weak. Due to those impacts, I often lose my consciousness in marketplaces, home and while walking.

I was a daredevil, but army torture simply deteriorated me.

My family also suffered with me. I lost my mother. Besides my eldest brother-in-law Ghulam Hassan Beg was gunned down by unknown gunmen when I was in jail. All my sisters are married now.

I have a 17-year-old daughter. My monthly income is Rs 2700, that too given by JKLF. But my treatment cost me much more.

***

To screen normalcy, government tried to open three of the total nine cinemas in Srinagar in later part of nineties. But a grenade blast outside Regal on its first day of reopening in 1999 not only pulled down its shutters, but also devoured one precious life.

After the incident, the government immediately closed the Regal. While Neelam and Broadway continued to run amid tight security before they made hotel out of Broadway.

Now, Regal is totally disintegrated to replay the movie that created a militant mood among masses. And the rebel has been rendered too weak to repeat what ‘immortalised’ his act.

Show might be over, but the showman lives on.

Perhaps, Omar Mukhtar was right, when he said: “I will live longer than my hangman.”